During the Chilean state coup of 11 September 1973, thousands of left-wing sympathisers, intellectuals, politicians and public figures were taken prisoner and held at makeshift concentration camps around the country. Many thousands were brought to the subterranean sports complex Estadio Chile.

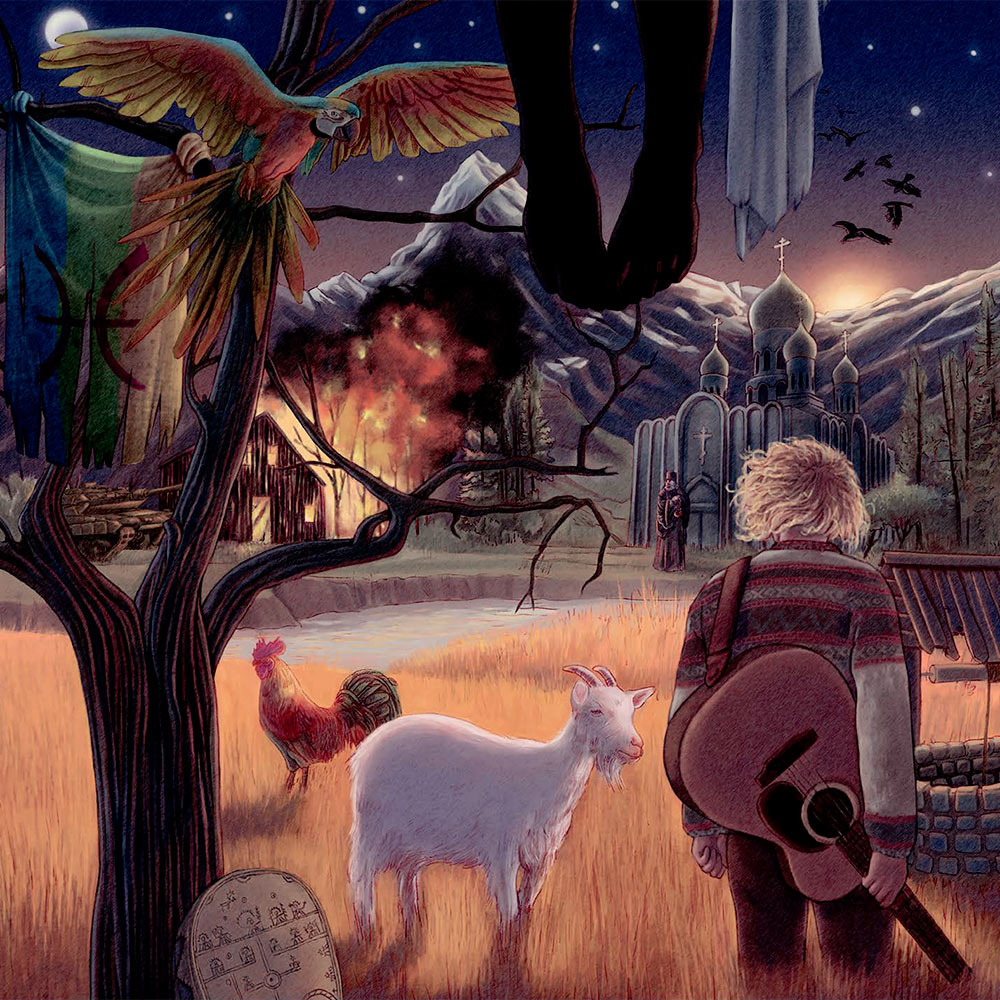

Víctor Jara was one of them. The famous singer and theatre director was one of socialist president Salvador Allende’s strongest supporters. He had dedicated his entire career to political activism through a life on stage, as well as behind it.

In Plegaria a un Labrador, Jara displayed both his political dedication and his artistic talent. As in many of his songs, he addresses the Chilean working class. Borrowing the form and style of the Lord’s Prayer, he encourages the people to rise up and realise their own power: “You can steer the course of the river. You, with the seed, sow the flight of your soul.”

“Blow, like the wind blows

the wild flower of the mountain pass,

clean the barrel of my gun like fire.”

Víctor Jara’s commitment to the political left cost him his life. In Estadio Chile, he wrote his last poem on scraps of paper. A few days after the coup, his wife Joan found his dead body on the street. She gave him a swift burial in the poorest part of Santiago’s enormous graveyard, and fled the country along with their four children and Víctor’s original recordings in her suitcase. For nearly twenty years to come, Jara’s music would remain forbidden in Chile.

Today, more than 40 years after his death, Víctor Jara’s songs are again sung in the streets, in factories, in family gatherings, and in concerts by young Chilean artists. Although Víctor Jara was murdered for his music, his songs live on.

---

Source

Joan Jara “An Unfinished Song”

Åsta Sirnes - En studie av Victor Jaras musikk i en chilensk kontekst.

Quote from Plegaria a un Labrador from the official translation by Adrian Mitchell.